In the early morning hours after talks to buy the phone business of Bouygues SA collapsed, Orange SA Chief Financial Officer Ramon Fernandez took to Twitter with pictures of vibrant flowers: An orchid, a begonia, an iris and a water lily.

In the early morning hours after talks to buy the phone business of Bouygues SA collapsed, Orange SA Chief Financial Officer Ramon Fernandez took to Twitter with pictures of vibrant flowers: An orchid, a begonia, an iris and a water lily.

“After three months of intense Jardiland, back to high-speed business with an incomparable Orange momentum,” Fernandez wrote Saturday, tagging his boss, Chief Executive Officer Stephane Richard. The night before, after markets had closed, the two sides had called it quits, giving up any hope of clinching a deal. After a nervous weekend for investors, the stocks opened with massive declines Monday.

Jardiland, a French gardening-supply retailer, was the code name assigned to the high-stakes talks to consolidate the French phone industry, according to people familiar with the talks. The orchid, the largest picture, represented Orange, the begonia was Bouygues, and two other carriers who stood to gain some Bouygues Telecom assets — Iliad SA and Numericable-SFR SAS — were iris and water lily, said the people, who requested anonymity discussing the private negotiations.

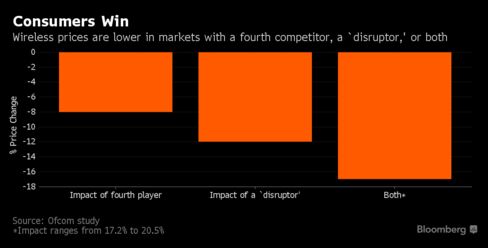

Success before a self-imposed April 3 deadline would have eased pressure on Orange, the former French phone monopoly and still the market’s biggest player, which along with Bouygues has been contending with a price war since Iliad, led by Xavier Niel, introduced its low-cost Free wireless service in France. Instead, the market remains split among four players, an anomaly in a European context that’s shaken out rivals through mergers.

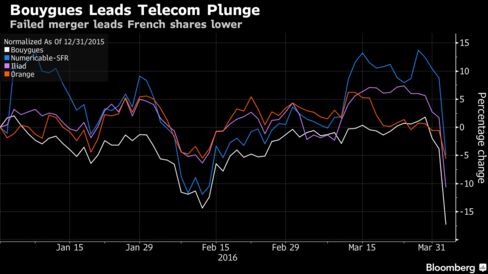

Investors felt the impact on Monday, when shares of Bouygues, Orange, Iliad, Numericable and its parent, Altice, were the five worst performers on the Stoxx Europe 600 Price Index. Orange declined 5.4 percent to 14.56 euros at 9:42 a.m. in Paris, while Bouygues dropped 14 percent to 30.19 euros. Iliad sank 13 percent to 195.40 euros and Numericable dropped 14 percent to 31.46 euros. The slump wiped more than 8 billion euros off the companies’ combined market value.

Richard was no stranger to forces of consolidation. Anticipating Free’s impact on his company, the executive had met privately with Bouygues Chairman and CEO Martin Bouygues four years earlier, seeking to link their businesses in response to the arrival of a disruptive new entrant. Bouygues dismissed the idea at the time.

Coming Together

But the seed for a combination had been sowed. After a second attempt in 2014 failed, Martin Bouygues and Richard revisited their plans one more time. The two men convened at Richard’s private office in one of the most elegant districts of Paris in late November, according to one of the people. The executives met two weeks after the city had been rocked by the terrorist attacks of Nov. 13 that left 130 people dead. Richard was visibly moved by the proceedings of the official mourning that he followed on television, and the men quickly found common personal ground, the person said.

Representatives for Orange, Bouygues and the government declined to comment on details of the talks.

Bouygues suggested tying together their mobile businesses, and negotiations started properly the following month. From the get-go, talks were complex: The French state remains the biggest shareholder in Orange, the country’s former phone monopoly, with a 23 percent stake. To address antitrust concerns, a potential post-merger entity would have to sell assets to the two other French mobile players, Iliad and Altice NV’s Numericable-SFR.

Through it all, Richard was the point person because executives from all the companies gathering in the same room would have risked violating antitrust rules, according to the people. He’d meet Martin Bouygues, then consult Iliad’s majority shareholder Niel and Altice. Both Richard and Bouygues were in touch with Economy Minister Emmanuel Macron and his team, notably Martin Vial, who heads France’s agency for state holdings, the people said.

On Dec. 7, the secret negotiations burst into the open when Bloomberg News reported that Orange was in early discussions about buying Bouygues’ telecommunications and media assets. It took another month for the two sides to officially confirm the talks.

French Resistance

Macron, a key government player, was initially open to a deal. All along though, he sought to ensure that jobs would be safe and that the government would keep its stake, or barely dilute it. Prime Minister Manuel Valls followed from a distance, with the odd meeting with Richard, and President Francois Hollande was also kept informed, the people said.

The more the talks advanced, the clearer it became to the participants that a deal satisfying all parties would be difficult to clinch.

Tough Demands

Among points of contention were Bouygues Telecom’s assets — shops, networks, customers, employees — and how they would be split and at what price. The complexity of several simultaneous bilateral negotiations was exacerbated by a clash of egos, personal dislikes and political considerations, leading to the talks dragging on.

The aim had been to seal a deal by mid-February, when Orange was due to present its full-year earnings. When the date lapsed without an accord, the two sides set a deadline for end of March, with the specter of failure hanging in the air for the first time: Bouygues warning openly that a prolonged process would begin to be detrimental to business.

As keen as he seemed to combine with Orange, Martin Bouygues never departed from a tough stance: he demanded a price of 10 billion euros ($11 billion) to part from his prized creation, and also asked an initial stake of at least 10 percent in Orange. The price tag was similar to what Altice had offered for Bouygues Telecom last year, a deal that got rejected by the owner.

A Bouygues representative said the company was entitled to ask Orange to pay the amount that was previously offered by Altice. Execution risk was the key issue that triggered the failure of the deal, the representative said.

On March 24, Macron met Richard and Martin Bouygues separately to present them with his conditions: a higher valuation for Orange shares as the base of the transaction, a cap at 12 percent for Bouygues’ potential stake in Orange, a standstill preventing Bouygues from raising its stake over a period of seven years, and a restriction on double voting rights for 10 years.

The two sides made one last-ditch effort last week, setting the end of the weekend to reach an accord. Even before that deadline ended, Orange and Bouygues ran out of road, each putting out short statements after European markets closed on Friday that they’d ended talks.

Bouygues said key sticking points included social guarantees for its employees, the level of its stake in Orange and related governance, execution risk and the valuation of its telecom business. A potential rejection by antitrust authorities also caused hesitation at Bouygues’ board, and an already complex deal became too messy after the other companies started to back away from agreements about asset purchases.

Over at Orange, CEO Delegate Pierre Louette summed up the mood at his company with a follow-up tweet to finance chief Fernandez’s message, posting a photo of a patchy lawn. Its caption: “Quite a lot of work in this garden too this morning!”

[“source-Bloomberg”]